|

In the Venezuelan story, The Golden Eagle, a relationship between two friends saves a life. The stories, “Gino; What the Psychic promised; and Caring; reveal the surprising power and significance of friendship.

0 Comments

I was five years old. The elementary school where I attended kindergarten was 14 blocks away. En route there was a wide, busy street and I worried about getting across it before the light changed so I was always relieved when I got to the other side. One morning, I left my house, closed the door to the apartment where I lived with my parents, and walked down the outside steps to the sidewalk. A boy I’d seen playing stickball with a bunch of kids was standing at the bottom, looking at me. He was eight or nine, big for his age. I stopped. Some of the kids on the block had yelled. “Yid” when they saw me. I asked my father what the word meant. “Some people don’t like Jews so they call them bad names. Ignore them.”

In November 1985, after seven months of dealing with a rare form of leukemia, a friend, seeing my distress, paid for me to see a psychic. “Maybe he’ll tell you about your illness.” She was so determined to help me feel better I agreed to go.

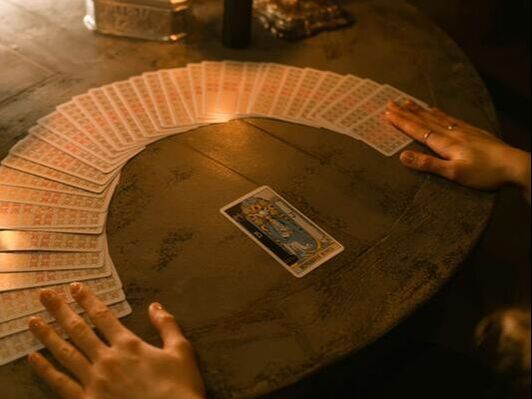

The man’s office was a pleasant room decorated with Oriental rugs and lots of flowering plants. He greeted me warmly, showed me where to sit at a table, and looked at me intently. “I think I’ll use the cards,” he said. I knew nothing about cards, but I nodded as if I’d made a choice. We met in 1991. I was her college professor and thesis advisor. As we got to know each other we discovered our fathers and paternal grandfathers had the same names and came from a similar area in what was then called Russia. We learned that we shared a passion for stories and making art, always searching for ways to make life meaningful. After she graduated, we became friends, staying in touch through visits, phone calls, and letters. The thirty-five-year age difference between us didn’t seem to matter.

For as long as anyone could remember, the tribe cherished the statue of Golden Eagle, given to them by god Ches for their goodness and wisdom. They were told to guard it well for it had magical powers but there would come a time when they would have to give it back. For generations the god’s gift brought victory and good fortune to the tribe. Then, a ruler died leaving no sons to rule. According to their law, a daughter could become the ruler. Because the young woman was wise and kind, she was accepted by the tribe who loved her gentle ways. She had not ruled for many moons when she became ill, so ill that nothing the tribe and their healers did—making medicines, creating brews, doing sacrifices, painting their bodies, performing special dances—cured the princess. One morning, she woke early and spoke to her dearest friend and companion. “Mistafa, god Ches appeared in my sleep. He asks that Golden Eagle be returned to his temple on the mountain peak. Only then will I be well.” Mistafa told the princess it was only a dream, but the princess was clear. “I am too weak to go. You must go in my place.” Mistafa was besieged with doubts and fears. “Who am I to approach a temple only chieftains visit? How will I find the way? What if I am not strong enough to carry Golden Eagle all the way?” The princess told her, “Do not be afraid for god Ches will support and protect you. He will show you the way. When you reach the peak of the mountain bury Golden Eagle at the side of the temple. Call out to god Ches three times. He will hear you. Listen well to what he says.” Mistafa wrapped Golden Eagle in a soft cloth and began her journey. Her arms ached from carrying the sacred sculpture. Her feet ached from the miles she walked. Seeing the mountain peak gave her new strength and energy. Using a sharp rock, she dug a hole deep enough to bury Golden Eagle, then cried out to god Ches three times. All was quiet. She fell asleep nestled in the cloth in which she had carried the sacred statue made of gold. When she woke the next morning, she saw what she had not seen before. Where she had buried Golden Eagle there was now a lovely bush covered with green leaves and purple blossoms. A voice commanded. “Gather leaves in the cloth and bring them to the healers. Tell them to brew a strong tea and serve it to the princess.” Mistafa did as she was told, then made her way back without stopping to eat or drink or rest. She brought the leaves to the healers who prepared the tea. With each sip of the strong brew the princess regained her strength and ruled wisely for many years. |

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed