0 Comments

Fundamentalism, be it religious, political, or any other kind all share one precept—believers are right, everyone else is wrong, and any and all questions are answered within the belief structure. If questions can’t be answered within the belief structure, the questions aren’t valid. Dialog is impossible because there is no doubt. Their truth is THE truth and everything they know or experience supports this. Since many fundamentalists grow up in family and social situations where there is no diversity of thought or experience. Their world is THE world.

Judie Fein wrote a piece for Psychology Today https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/life-is-trip/202101/why-you-cant-change-anyones-political-opinions about the impossibility of changing someone’s political beliefs, but the same is true for all deeply held beliefs, which give structure and meaning to the believers’ life. So, is changing someone’s belief impossible? No, but the best, perhaps only way for someone’s belief to change is for the person to experience a transformative event in their lives, and even then, it usually doesn’t happen quickly or easily. The occurrence, which must be life-changing, might be a family confrontation, cataclysmic illness, leaving family to go to school or one’s hometown for work, or experiencing a powerful contradiction in what was formerly assumed—all changes where the person meets people whose ideas and experiences differ radically from her/his own, discovering that the world is profoundly different from the one in which he/she grew up or live in. Lately, relatives of people espousing hate-filled beliefs have contacted groups like Parents for Peace, asking for help. The process of shifting hate-filled violence to being part of a caring community takes time, listening without judgment, building trust, and above all, the person’s readiness to participate in the process. My experience with a strongly engrained belief is benign compared to hate-filled beliefs, but even so, it was difficult to change. I learned early on not to ask for help, that it could be dangerous, even life-threatening. My father often told me, “You’re strong, you can manage,” and mostly I did. But when I was diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia it became impossible for me to “manage.” When I came home from the hospital, I wasn’t strong enough to take out the garbage. And yet, even when I knew I had to ask for help, I did my best to avoid it. One big problem was that I lived 2 ½ hours from the cancer treatment center, too long a drive for me to do by myself. I hated having to ask people to drive me—at first, once a week, then twice a month, then every three months—for years, which meant asking a lot of people so as not to wear out my welcome, as well as figuring out ways to thank them. One day, in despair about having to ask for driving help, I searched for a way to get to the treatment center by myself. I flew from an airport in Wilmington, DE to an airport in Baltimore, MD. A driver from the treatment center picked me up. After treatment, which included five bone marrow biopsies on each side of my sacrum, I wanted to go home. I needed to go home. I didn’t care about anything except going home. The medical people told me this was not only medically unwise, a hurricane was predicted. The medical staff told me to stay overnight, that I could go home in the morning when flights resumed. Their arguments were sensible and reasonable, yet all I could think about was going home. Nothing anyone said changed my mind. So, despite the staff’s obvious disapproval, a driver took me back to the airport in Baltimore. And, as predicted, a hurricane grounded all flights. I sat in a chair in the waiting room. A woman passing by told me blood was oozing on to the floor. Embarrassed, I thanked her, wiped up the blood with my dark skirt and went into the bathroom. Blood was seeping from the biopsy wounds. I staunched them as best I could and put paper towels on the chair. When the hurricane passed, my scheduled flight was permanently cancelled and my new flight was routed to Philadelphia, PA. I was beyond caring about changes. At least I was on my way home and could take an airport shuttle home. Once the plane took off, a flight attendant noticed there was blood on the back of my seat and gave me a towel to wipe it up. I pressed my back against the chair as hard as I could to staunch the bleeding. After hours of difficult traveling, when I finally got home, I flopped into bed, relieved my ordeal was over, that is until I needed to use the bathroom. When I got up out of bed, I was so dizzy from loss of blood I had to crawl to the bathroom. This was when I finally accepted there were times when I had to ask for help, that this was not dangerous, nor did it mean I was an incapable person. What would it take to change your belief?

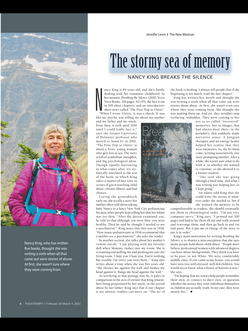

Nancy King was hosted by the Santa Fe Public Library in an online author event to share her stories, some of which can be found in her memoir, Breaking the Silence. She gave a behind-the-scenes peek at how her memoir unraveled from the images in her head and answered some hard-hitting questions about coping mechanisms, forgiveness, and the path to healing.

The following story illustrates why I think the question is: How do I respond to violence?

The Son who wanted Revenge (Buddhist) There was once a king who attacked a neighboring country, killing the king and queen and many of their people. The king could not make himself kill the baby son of the couple and took him home to raise as his own son, a prince. The child grew up feeling loved by the parents he thought were his birth parents. Yet as he grew older the prince heard whispers and murmurs about a long-ago battle, about a baby boy rescued. In time, he confronted an old courtier and asked about the long-ago battle. At first the old man refused, but the prince persisted. “Tell me what you know,” he pleaded. In time, the old man told him how the king had attacked the neighboring country, that the man he knew as his father was the king who murdered his parents. The prince was filled with rage and decided it was his duty to kill his adopted father. He made and discarded many plans until he created one he knew would work. Every afternoon his adopted father sent his guards away and took a short rest. The prince sharpened his sword and prepared to act. The next afternoon, when he saw the king sleeping soundly in his royal chair, the prince moved behind the chair, lifted his sword and . . . Try as he might, he could not bring himself to lower the sword. The king awoke suddenly and saw his son with the sword raised. “Why do you have a sword in your hand?” “I know you are the man who murdered my parents. It is my duty to murder you, to avenge my parents’ deaths. But, to my great shame, I am unable to bring down my sword.” The king told his son to put the sword by his chair and sit beside him. “You have acted wisely and with compassion. Had you killed me my other sons would have felt it was their duty to kill you. When you have sons, they would feel it their duty to kill those who killed you. By being willing to lower the sword, who knows how many lives you saved today?” I share this story because it reminds me; we have choices. We can choose revenge and continue the cycle of violence or we can choose to do what we can to stop the violence, by deciding not to kill or maim. It takes courage and wisdom and emotional strength to resist taking revenge, which might feel good in the moment, but doesn’t bring back those who are dead. How we react to people around us makes a difference. When I was 19, I was hired to be a recreational therapist in a large mental hospital, in charge of a building of 300 women. I knew nothing about mental illness and received no training prior to beginning work. A chance encounter with an attendant in charge of a building housing violent women, who asked me to work with her patients, was a request I didn’t know how to say no to. I was frightened. I knew the previous recreational therapist working with the violent women had been beaten up so badly by patients she was hospitalized with life-threatening injuries. I didn’t know why they beat her up. I didn’t want to find out. I decided I would treat these “violent” women exactly as I did the patients in my building, as if they were healthy—whatever that meant, treating them with respect and kindness. The women responded with gratitude, letting me know how thankful they were to be out with me. I never felt threatened. I was never hurt. Much of the violence in the world is beyond our control. What is in our control is how we choose to live. Hate begets hate. Violence begets violence. Only lovingkindness—person to person—can stop the seemingly endless cycle of violence. What is your response to violence? |

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed