|

All my grandparents emigrated from what was then known as Russia in the early 1900’s. None of them wanted to come to the United States. Forced to flee from pogroms, anti-Semitism, discrimination, the Tsar’s army, (which meant 25 years of conscription for Jews) and political tyranny, they came to a country that did not welcome them. My grandfathers were not vocationally prepared to earn a living. My grandmothers’ talents could not overcome the obstacles of gender, language, prejudice, education, opportunity, and financial instability.

After writing my memoir, Breaking the Silence, published in 2020 by Terra Nova Press, I thought about the traumas my grandparents experienced and the difficulties of my life with my parents. I wondered what, if anything, had been passed on, intergenerationally, to me. As I wrote what I knew about my grandparents and parents, I discovered patterns that hadn’t been obvious before. What do you know about your ancestors? How do you know what you know? Did you think to ask them about their lives while they were still living? Do their lives matter to you? What, if any, influence does their experience have on you?

2 Comments

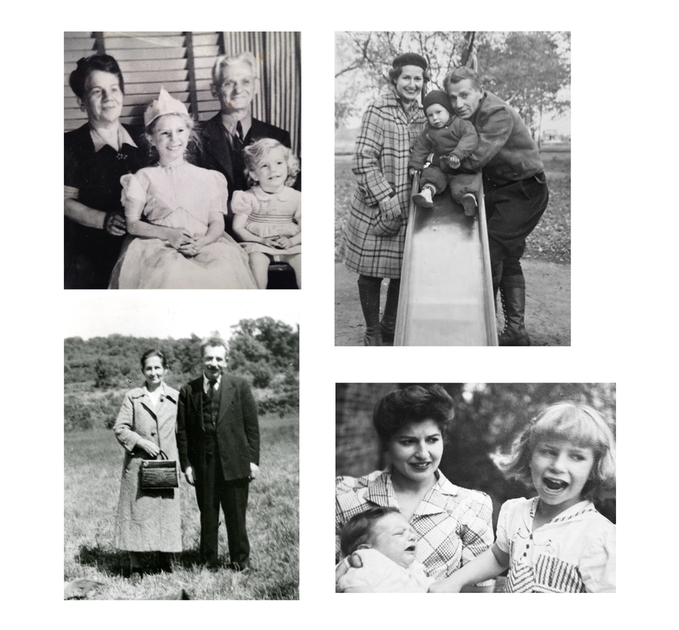

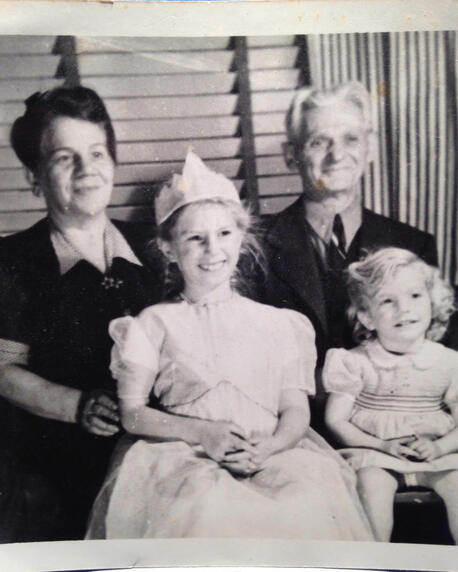

Father’s family Note: My mother hated my father’s family, which made it virtually impossible for me to know my grandparents. If I said anything good about them in my mother’s presence, she punished me. I learned to say nothing, do nothing, sit quietly, and eat as little as possible the few times I visited them, with or without my mother, but always with my father, never alone. Most of what I know about them comes from stories told by my father, his sister, and his two brothers, the youngest of whom was 20 years younger than my father.

I know very little about my parents’ lives before they married. They never offered information and I never asked. I know that my mother and one of her sisters changed their name from Kurinsky to Curran in order to find work. Having a Jewish name triggered anti-Semitism. When my father died, my mother gave me letters my father had written to her, mostly before they were married. I learned she and a friend hitchhiked to the Grand Canyon when she was 18, and told my father not to tell her parents. He saw how upset her parents were and told them where she was, much to my mother’s fury. In a letter written after he learned of my mother’s anger, he says she is like two people, one kind and caring, the other angry and unpleasant. According to my father’s sister, she and my mother were friends, but after the marriage, my mother stopped being her friend. My parents liked to go to dances, and, when they could afford it, go to theatre, art exhibits, and concerts.

According to the letter my father wrote when my mother was pregnant with me, something happened to cause my father to send her to a farm for a few weeks where she could relax and feel better. This was not something struggling Jewish families often did. My Uncle Dave told me my mother hated being pregnant and blamed “the thing inside me” for losing her shape and causing her such distress. For years, I used the Chinese tale, “Li Chi the Serpent Slayer,” in my teaching. One of the students’ tasks was to choose a moment in the story that resonated and explore why it mattered. For years I picked the same moment, when Li Chi, after slaying the serpent, goes back into its cave and finds the bones of the girls previously sacrificed to keep the village safe from the serpent. She brings the bones back to the village for burial with full honors and acknowledgement of what the villagers had done. For years I didn’t understand why this moment mattered so much until one session, without thinking, I fingerpainted images of people in black and a small blob of yellow, isolated, as if looking at the black images. After the painting, when I quickly wrote: life, abuse, power, I finally understood the meaning of the moment for me. I was ready to go into the metaphorical cave to face the bones of my past.

|

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed