|

I was enjoying teaching, writing, and directing plays for children, but I felt as if the world owned every piece of me. I needed to do something creative that I could do for and by myself, that didn’t depend on anyone else’s schedule, needs, wants, or wishes. I thought about painting, which would fit into my tightly scheduled life, but when I painted, what came out of my fingers can only be described as ferschtunkenah, a word I made up, that sounded like my paintings looked—awful. But, the urge to make something was too strong to ignore. Ceramics was out. Too messy in a small house, with no place to store or use clay. I had no money to invest in jewelry-making, even if I had the talent, which was doubtful.

A friend told me about a weaver with a great sense of humor who was going to teach at the Delaware Arts Center. “She could even teach you,” grinned my friend. I was so desperate to find a creative outlet, something just for me. I signed up. I had never thought about weaving but the course wasn’t expensive and it fit my schedule. The weaving teacher focused on process. Eleven of the twelve of us who signed up wanted to weave placemats. They were unhappy. I reveled in the freedom of process and looked forward to learning more. Toward the end of the course, only four sessions of which focused on weaving techniques, the eleven placemat weavers quit and the remaining sessions were cancelled. As important as the few weaving techniques I learned, was the realization I couldn’t weave on a traditional loom with moving parts that clanged as the shuttles and heddles and treadles went up and down, in and out—the feet doing one thing, hands doing another, and who knows about the mind. Coincidently, a man who lived in my community asked if I’d befriend his wife, a professional weaver from Norway. I found her difficult and wasn’t surprised when he told me his wife had left him. He said he’d had a loom made for her that she’d never used, a tapestry loom, essentially a big picture frame with no moving parts. I asked to borrow it. Even warping (the vertical threads on a loom) was different. Unlike a conventional loom, where warping is a continual process, with equal tension until you have the length of warp needed to make the finished product, I had to put each piece of yarn on separately and tie it off. My warp was sometimes four and a half feet long and about five feet high. By the time I finished warping, the threads I put on first had loosened so I had to tighten them, but I was never able to make the tension on the warp threads consistent. I learned to accept and use the varying tension in the warp. When a weaver takes off a piece from a conventional loom the weaving is flat unless the weaver has added texture. When I take a weaving off, the uneven warp tension creates texture and is never flat. I had to learn to enjoy my imperfections as a weaver working on a less than perfect loom. After I put my first warp on the loom and began weaving, I realized I didn’t want to give the loom back, despite its funky design. It had been made by a carpenter who’d never seen a weaver weave. The loom had no lateral stability, no vertical strength, and the roller had no stops. No wonder my friend’s wife never used it, yet it was perfect for me. No moving parts. No clanging noise. No stress. I asked if I could buy it. “You have no money,” he said, which was true. We settled on a can of cookies, a loaf of bread, and a weaving. It took some years before he got his weaving; we became friends. I turned the loom around, stored my yarns on the roller, and figured out how to stabilize the loom laterally, and strengthen it vertically. Using the four techniques I learned in 1968, I continue to weave quietly, slowly, with fingers and a fork, choosing handspun yarn with texture, creating patterns as I work. If I don’t like what I’ve woven I unweave. If I like what I’m weaving I keep going. If I run out of one kind of yarn, I find ways to incorporate other yarn. I weave without a plan, without expectation or schedule. The process is slow. There is no way to weave fast on my loom. If I feel speeded up inside myself, as soon as I begin to weave, my inner world slows down. I’m focused on color and design and texture. For the moment weaving is my world—a respite from problems and pressures. Before I even made my first weaving I decided I would weave to please myself. If people liked what I wove, fine. If they didn’t, fine. I refused to take commissions or sell what I made. Instead, I give weavings to friends and family. Although I couldn’t paint with paint, I ended up learning to paint with yarn. What is it that you do for yourself? For your satisfaction? Free from others’ comments?

0 Comments

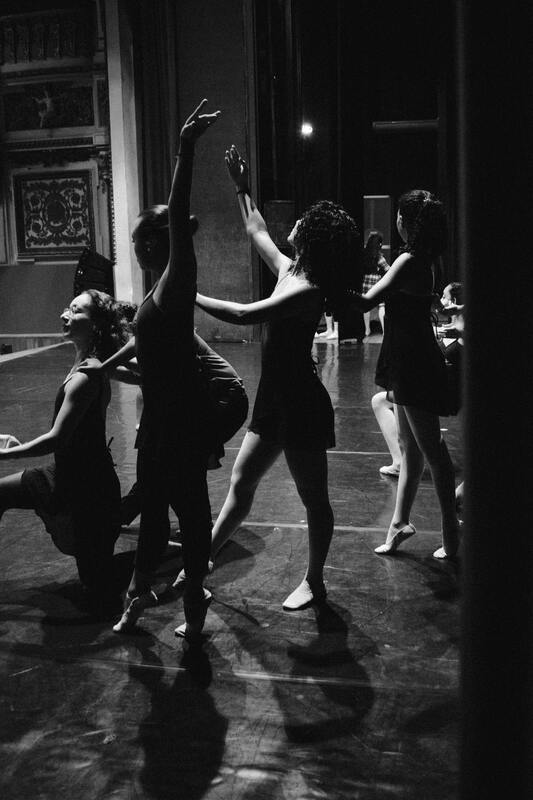

I was a single mother, with no income, no health insurance, and no child support. I needed a full-time job. Badly. But, I’m not good at doing what I don’t want to do, and what I didn’t want to do was teach physical education or Junior High Science—both of which I was credentialed to teach. Given all the years I’d been teaching dance, when I saw an advertisement for a position teaching dance at Swarthmore College I immediately applied, paying no attention to the ache in my stomach as I sent off my résumé. I still had a bad feeling about dancing and choreographing after my experience at the University of Wisconsin where the two dance professors and I were in continual conflict about the worth of my dance ability and choreography—a conflict I first experienced as an 8-year when my ballet teacher refused to let me dance the dance I created for the annual spring concert. She said it wasn’t beautiful and dance had to be beautiful.

Elated to be invited to teach a master class as part of the interview process, I paid no attention to the nausea I felt as I walked to the studio. I told myself how I felt didn’t matter. What mattered was the secure position, doing creative work, good salary, and benefits. Students walked into the dance studio and began warming up. One young woman came up to me and asked if I was the new dance teacher. “I hope to be,” I said, hoping my grin was not a grimace. She wished me good luck and joined her friends. They stared at me. Time to begin.witch up I told the class I would like them to move as they felt inspired by the story I would tell them. The students looked startled, but started moving in their own ways as I related “Hummingbird and Panther,” a world tale from Brazil, about Panther who wants Hummingbird to poke mud out of his eyes. Hummingbird is afraid he’ll eat her, but his distress overcomes her fear. When Panther can see he expresses surprise at how drab she is. Hummingbird is affronted, but Panther offers to help. She decides to trust him once again. After doing what he tells her to do, Hummingbird flies to the river to look. Her trust has been rewarded. She is now as colorful as she yearned to be. After telling the story I asked the students to take an aspect of the story that intrigued them and create a movement sequence, either by themselves or with one or two others, using found sound or any of the musical instruments in a box in the corner of the studio. They quickly began to create, intensely focusing on the assignment. When I asked them to share their work, one woman with long dark braids asked, “You going to judge it?” “No. I’m not into judging, but if you want help in deepening your work, let me know.” She looked suspicious but volunteered to be first. Her work was wonderful, as was what followed. After the last group finished, the woman with braids said, “We never did anything like this before. It was fun. I hope you get the job.” I flushed, thanking them for their wonderful participation. This time there was a real smile on my face, and no stomach ache, as I watched them leave. After a brief lunch with the dance teacher who was retiring, she walked me to the Dean’s Office to meet with the Dean. Before parting she told me she’d heard really good comments about the class and was sure I’d get the job, that the other interviewees had not been as interesting or innovative. The Dean, a woman in her 50’s, with twinkling blue eyes, welcomed me into her office, and offered me coffee and scones. Like the retiring dance teacher, the Dean told me she’d heard wonderful comments about my teaching. I relaxed, sure I would get the job. As we sipped and munched she asked me about my life, what interested me, how I’d thought to create the kind of class I’d taught. Disarmed by her friendliness and interest, I told her how I taught dance to “underprivileged” children, helping them to find words as well as movement to express their feelings,” that I’d started a children’s theatre group in a Black community center, writing and directing plays where action mattered as much as words, how I used movement to tell stories. I told her about the acclaim I’d had as a choreographer working with young adults. All the time I talked she nodded and smiled, asking questions that encouraged me to articulate my view of teaching dance performance and choreography. Just when I thought she was going to hire me she asked, “You don’t really want to teach dance, do you? I was too stunned to lie. “No, I don’t” She spoke kindly, caringly. “I’m going to do you a favor. I’m not going to recommend you for this position even though you did a fine job teaching the master class and you have wonderful recommendations.” My distress was too spontaneous to hide. “It’s not what you think,” she said. “Then what?” I managed to blurt out. “I’ve listened to you talk about your interests, your previous work, how you create. I don’t think you want to be teaching dance. I think you want to teach movement and create theatre pieces. If I recommend you for this position, you’ll be teaching something you don’t really love. I can’t do that to you. You’re a wonderful teacher, a woman with marvelous creativity and ingenuity. You need to follow your heart as well as your mind. It may not feel like this right now, but I’m doing what’s right for you professionally. I’m sure you’ll find a way to teach what you love.” Nine years before, I’d had a technical scholarship to study dance at the Connecticut College Summer Dance Program. Tom Watson, the technical director, was demanding, with a lot of dance prima donnas to light, costume, and care for. I worked diligently, carefully following his instructions, ready to do whatever needed to be done. At the end of the summer he said, “I don’t know how or when I’ll repay you for your hard work, but I owe you.” Now, nine years later, stunned by the loss of the dance position, but realizing the Dean had seen into my heart, I made an appointment to see the new Chair of the Theatre Department. The sign on his door read, “Dr. Thomas Watson.” I gasped in amazement. He remembered me from when I’d worked for him nine years ago, and asked how he could help. With his support I earned an MA in Theatre and was then hired as a part-time instructor. Twelve years later, after promotions, authored articles, books, and plays, and teaching both abroad and throughout the US, I became a full professor in Theatre. When the Dean refused to hire me, based on my uncensored talking and her sense of what I really wanted to do, I felt ashamed that I’d revealed myself to her, in despair as to how I could do what I loved and still support my son, wondering if I’d ever find a way to do the work I loved. At the time, actors studied ballet and other forms of dance to improve their physical ability. I was one of the first people to create courses in movement for actors, explore emotional projection, and use traditional stage blocking as a way for actors to express inner thoughts and feelings. The Dean’s refusal to hire me was an unexpected, albeit painful gift, that made possible a 34-year university career where I created almost all the courses I taught. Have you ever experienced a rejection that led to something new and unimagined? What was that like for you? When I was three-years-old I became one of the designated entertainers for my six-year-old cousin Rose who’d been stricken with polio. I had heard my mother and others talk about how lucky it was that Rose didn’t die. I wasn’t sure what die meant, but the way my aunt and mother talked about Rose dying didn’t sound good. She lay in bed, motionless. I sat in a chair next to her bed, trying to think of things to say that would interest her or make her laugh. I wasn’t very good at telling jokes and half the time I couldn’t remember the punchline. This made her mad. She told me I needed to learn to tell jokes but I had no idea how to do this. Since I couldn’t think of anything else to say, and was tired of sitting, I left the bedroom and went into the kitchen where my mother and aunt were drinking coffee. My aunt told me to go back, that Rose needed company. When I stood there, unwilling to leave the kitchen, my mother scolded me. “Nancy, you’re always telling stories, go back and tell Rose a story.”

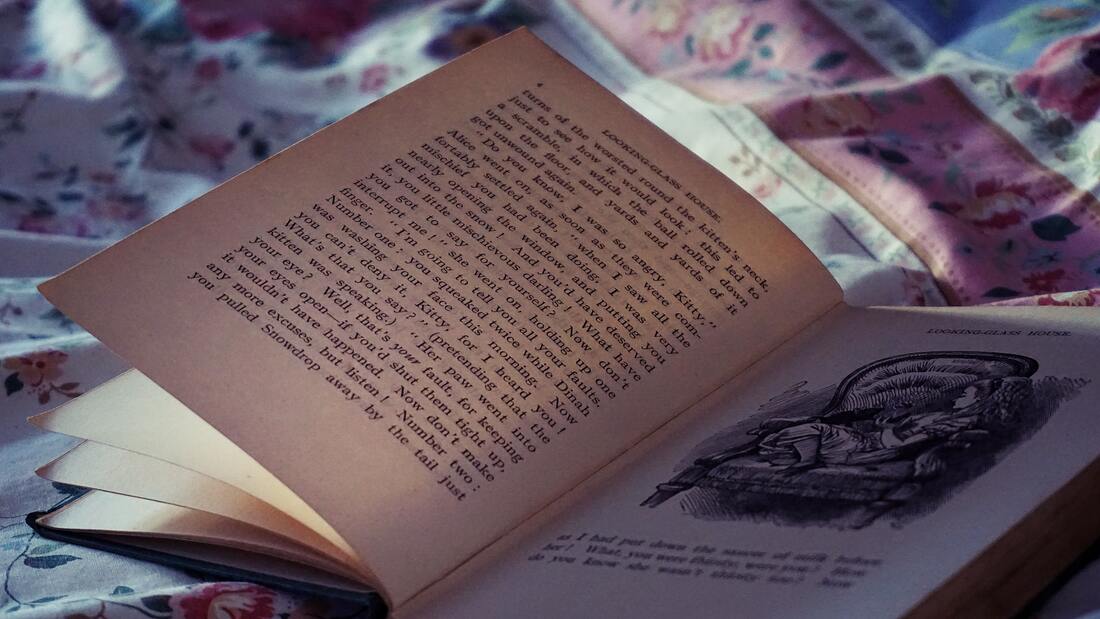

I walked to the bedroom as slowly as I could, hoping she’d be asleep, but she was awake, waiting for me. I told a few stories as best I could but Rose soon let me know she was bored with my stories. “Read to me,” she said in a voice that frightened me. “I don’t know how to read,” I admitted, scared of what she’d say. She looked angry and made a terrifying chest noise. It sounded like what people described when they talked about her dying. When she caught her breath she said, “Reading is easy. I’ll teach you.” I don’t remember how she taught me, but I was desperate to learn as quickly as possible. I didn’t want to be the one who made her die. I must have learned fast enough and well enough to suit her, because when I started reading, she stopped complaining about my reading. The only problem was that sometimes I didn’t know a word and stumbled. Disapproving of my mistake, she made the horrible chest noises that petrified me. I panicked. What would they do to me if my cousin died while I was reading to her? The sounds she made when I mispronounced a word scared me so much, the next time I didn’t know a word, I made one up. Since she couldn’t see the book, she didn’t know the difference. I began to enjoy reading to her, making up half of what I read. No mistakes. No terrible chest sounds. No die. Big relief. How did you learn to read? |

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed