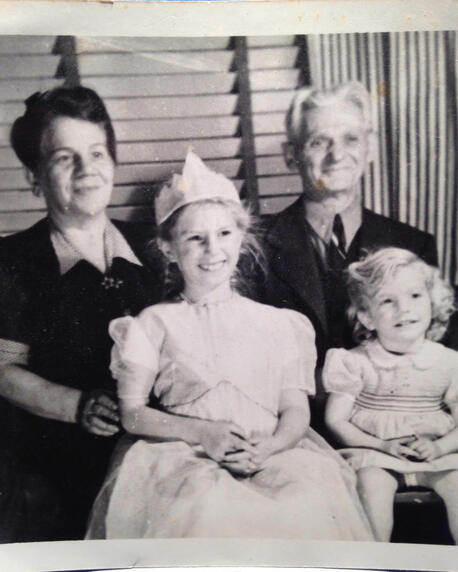

Father’s family Note: My mother hated my father’s family, which made it virtually impossible for me to know my grandparents. If I said anything good about them in my mother’s presence, she punished me. I learned to say nothing, do nothing, sit quietly, and eat as little as possible the few times I visited them, with or without my mother, but always with my father, never alone. Most of what I know about them comes from stories told by my father, his sister, and his two brothers, the youngest of whom was 20 years younger than my father. Grandfather: My grandfather’s father was an orthodox rabbi in Russia (probably Byelorussia). His mother died when he was young and his father’s second wife didn’t want to spend scarce resources on another woman’s children. The village was too poor to help them. To escape their stepmother’s cruelty, my grandfather and his younger brother ran away, supporting themselves by doing odd jobs and repairing roofs. One day, as they were working on a roof, my grandfather’s younger brother fell off and died. Nearby Cossacks laughed. My grandfather, in his grief and fury, threw rocks at the Cossacks, then found a way to escape their rage and murderous attempts to kill him. His hair turned white. Some say he stowed away, others say he ran all the way to the boat that took him to the US. He went to Minneapolis, found it too cold, and returned to New York City. He married my grandmother and earned a living hand-rolling cigars until cigarmaking was automated. With no vocational skills he became a nightwatchman. Although he had little formal education, he spoke Polish, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. I was his first grandchild. At the time of my birth, my parents and I lived near my grandparents. My father’s sister told me, after my mother died, that when my mother found my grandfather looking at me in my carriage outside of where we lived, my mother told him if he came again without letting her know ahead of time, she’d call the police. When he and my grandmother visited for Chanukah, my grandfather would surreptitiously slip two quarters into the pocket of my dress. We both knew that if my mother saw him do this, she would demand I give the money back. I felt ashamed by the harshness in her voice, as well as her words, when she’d say in front of them, “Give the money back. They can’t afford to give you Chanukah gelt. I remember my grandfather as a gentle man, with a loving smile, a twinkle in his eye—a man who seldom spoke. Grandmother: My grandmother’s father was a Yeshiva Bocher—a life-long student of the Talmud. Her mother supported the family as was the custom. My grandmother desperately wanted an education, but as a female, was not included in the teachings of her father with her brothers. She decided to sit outside the door and listen. One day her father came out and tripped over her. “What are you doing,” he asked. “I’m learning,” she said. He soon realized, after questioning her about what she knew, that she was the smartest of his children and included her in his teaching, a rarity in those days. Even after she came to the US, she never lost her love of learning. She regularly asked my father to get books for her from the Public Library in Manhattan. How many mothers ask their sons to take out Nietzsche translated into Yiddish? My grandmother, even as a young girl, was a socialist, actively joining with other young people to fight the Tsar’s injustices. At night, she would go out and help those injured in battles with the Tsar’s soldiers. One night, as she was about to return home, her father found her and said she couldn’t go home, that soldiers were there, waiting to arrest her. Her given name, Hinde Kerschner, became Helen Horn on a forged passport. She traveled to Moscow hidden in a hay wagon, and from there, made her way by boat to New York City. She was not yet sixteen years old. My father’s youngest brother told me she remained politically active all her life, working for social and economic justice. He recounted a time when the butcher raised his prices to the point where women like her couldn’t afford to buy. My grandmother organized a demonstration. She wore a blue hat and when a woman came out with a chicken, my grandmother grabbed the chicken, threw it and the blue hat over the fence behind her where another woman was waiting. When the police came to investigate, they asked if she had seen a woman wearing a blue hat. My grandmother, who was wearing a red hat (which had been hidden under the blue hat) said no. The chicken was divided equally among the women participating in the demonstration. When we went to visit her, we had to climb up many flights of stairs to their apartment. Not wanting to wait, my grandmother always came down the stairs, eager to meet us. She lovingly hugged me, saying what sounded like, “Mein sheyne maydele,” my pretty little girl. When my mother was with us, I could feel her anger, her piercing stare. I was afraid to hug my grandmother back. In spring of 1942, my grandmother received a letter from an old school friend. The letter, written in Yiddish, was stained with tears. The friend, who had been taking care of a sick relative, and was not in the village when the Nazis came, wrote to tell her that all of my grandmother’s friends and relatives were murdered by the Nazis at Babi Yar in late 1941. My father’s sister and two brothers were a close family, celebrating Seders, weddings, Bar/Bat Mitzvahs and other occasions. My father went when my mother was willing to go. I seldom attended, not wanting to be in my mother’s company. Although I occasionally saw my aunts and uncles, I grew up not knowing them or my cousins. Visiting my grandparents was always stressful. If I said anything good about them my mother attacked me when I got home. It was easier to be as quiet and unobtrusive as possible while I was with them. After my parents died, my father’s middle brother, Dave, told me my grandmother was so upset about my behavior she asked her three grown children, when my father wasn’t there, “What are they doing to that child? She’s like a stone. She doesn’t eat. She doesn’t talk. She doesn’t laugh. She just sits on the sofa with her coat on.” When I asked my uncle what they responded, he didn’t answer. My father’s siblings adored my father. No matter what I asked, none of them would say anything but good things about him. If they didn’t want to answer my question, they changed the subject. I remember my grandmother’s loving hugs, her whispering, “Mein sheyne maydele,” whenever she saw me. Mother’s FamilyGrandfather:

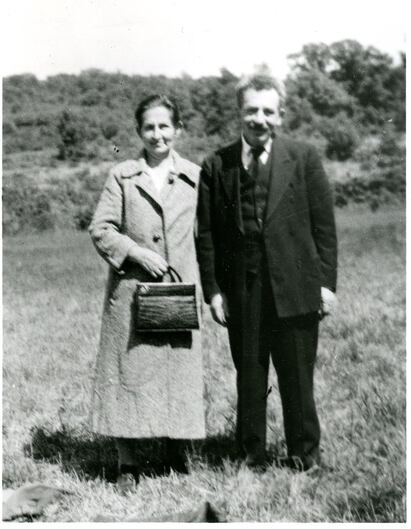

My grandfather grew up in Russia, in an orthodox Jewish family that treasured learning and the arts. He became a Yeshiva Bocher, a Talmud scholar, whose wife, already chosen, would support the family. When he was conscripted into the Tsar’s army, (twenty-five years of service for Jews), my grandfather’s family helped him to escape, which meant leaving behind the scholarly life he yearned to live, his wife-to-be, family, and friends. He arrived in the US with no vocational skills, to a country that valued materialism over intellectualism. In order to support his seven children, he painted houses and did odd jobs, but his lack of occupational prowess made the family’s financial situation precarious. The competition for scarce resources affected all of their children. Some married early to leave the family. One was determined to be rich. Another, though financially secure, never had enough. The only son left as a teenager. I remember my grandfather, who died when I was six, as a quiet man who loved to tell stories of books he’d read, of operas he’d seen, of theatre he’d attended. Grandmother: My grandmother wanted to own her own store, which was not possible in Russia; Jews were not allowed to own businesses or property. She came to the US with a sister and brother and worked for her brother, who owned a grocery store. She died when I was two, after a long illness. The stories told about her by her seven children, six girls and a boy, which she had in fourteen years, vary, depending on the teller. Some talked about her sharp tongue, others, her favoritism, some, her dislike of her children’s mates, others, her focus on making money. None spoke about her fostering an interest in education. While the stories about their mother differ, varying on the sibling, the tone was the same. The family was poor, unhappy, and, from what I heard, there was not much love to go around. Neither of my maternal grandparents were able to live lives of their choosing. Their financial struggles and unfulfilled lives might have contributed to their dying so much earlier than their siblings or my paternal grandparents.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed