|

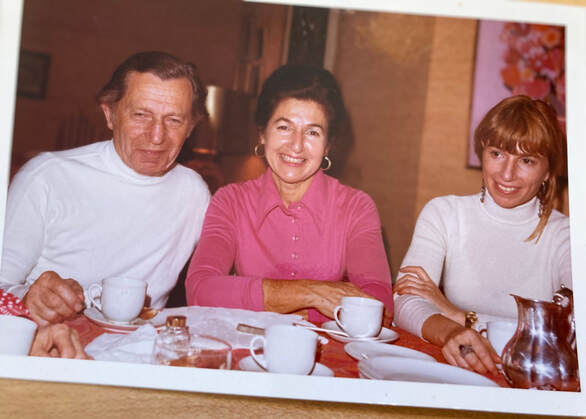

I know very little about my parents’ lives before they married. They never offered information and I never asked. I know that my mother and one of her sisters changed their name from Kurinsky to Curran in order to find work. Having a Jewish name triggered anti-Semitism. When my father died, my mother gave me letters my father had written to her, mostly before they were married. I learned she and a friend hitchhiked to the Grand Canyon when she was 18, and told my father not to tell her parents. He saw how upset her parents were and told them where she was, much to my mother’s fury. In a letter written after he learned of my mother’s anger, he says she is like two people, one kind and caring, the other angry and unpleasant. According to my father’s sister, she and my mother were friends, but after the marriage, my mother stopped being her friend. My parents liked to go to dances, and, when they could afford it, go to theatre, art exhibits, and concerts. According to the letter my father wrote when my mother was pregnant with me, something happened to cause my father to send her to a farm for a few weeks where she could relax and feel better. This was not something struggling Jewish families often did. My Uncle Dave told me my mother hated being pregnant and blamed “the thing inside me” for losing her shape and causing her such distress. My father was 29, my mother, 26, when I was born in 1936. According to my mother, when the nurse brought her her newborn, my mother said it couldn’t be hers, the baby was too ugly. The nurse looked at the name tag, realized she’d brought the wrong baby, and returned with me. My mother said I was uglier than the first, could she have the first baby. My mother thought this was a funny story. A few months later, my mother, worried about my weight, prodded my father, a pharmacist, to make an appointment with a well-known pediatrician. The doctor told my parents I was thin and healthy, but my mother needed to see a psychiatrist. My mother, when she told this story, was outraged. “Imagine wasting so much money for nothing!” When I looked at photos my father took, I realized, there were no photos of my mother cuddling me. In every photo of the two of us, she is holding me away from her. There is no visible emotional connection. My father worked long hours so I was mostly alone with my mother. My father’s sister told me that my mother “offered” to let her take care of me on Tuesday afternoons, but when my aunt said she had to work, my mother angrily told her that she’d just lost her chance to know her niece. I was eight months old when I was sent away from home for the first time. I lived with my Aunt Celia, my mother’s second oldest sister. In 1993, I did an EMDR session (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, a psychotherapy that enables people to heal from the symptoms and emotional distress that are the result of disturbing life experiences). I see my father fondling me with his penis. My mother comes in and starts screaming at me, “He’s mine, not yours. I’m gonna kill you.” She tries to grab me from my father. My father holds me away from her, puts me in a crib, then leaves with my mother. When the therapist asked how old I was I automatically said, “8 months.” When the session ended, I was in a daze. How could this be a memory? And yet, this experience fit the pattern that became more evident as I grew older and remembered more. When I was two my mother pushed me down stairs that separated our apartment from the one on the first floor where a retired policeman lived with his wife. He took me to the hospital. Soon after I was sent to live with my mother’s cousin Frieda. When I was four, my mother had just set the table for a dinner party. I tripped and grabbed the tablecloth, spilling dishes, glasses, flowers, and napkins. My father came home to find my mother choking me. He pulled her off of me, calmed her down, then they left the room. The next day my father drove me to New Jersey, to her oldest sister Ida. I lived with Ida, her husband Walter, and their two children for almost a year. During that time my uncle sexually tortured and abused me during the night. Since I slept in an alcove off their bedroom, he had easy access to me. When my aunt woke and asked what was going on, he told her, “Nothing. Go back to bed.” I had my 5th birthday party there and then was allowed to come home. My mother took out her rage on me, using me as her personal punching bag, throwing me against walls, appliances, floors . . . She broke bones and dislocated joints, always blaming the injuries on my carelessness. In some cases, my father set the bones and dislocations, but when I was seven, he took me to an ENT who said my broken nose needed surgery. When told how much it would cost, my father decided it was too much money. “She can breathe through her mouth,” he told the doctor. I was almost six when my sister was born. I loved playing with dolls and now, having a real live baby doll to play with was the best. I watched over her, making sure no one hurt her. My mother was not physically affectionate so when my sister started looking to me for hugs and cuddles, my mother took her jealousy out on me. When my sister broke my Nancy doll my mother comforted my sister. When my sister tore up all the papers I’d created for my “school,” my mother comforted my sister. My mother engineered a rupture between my sister and me that has lasted all our lives. I was quite young when my mother told me that I was responsible for making her life meaningful. Since I had no idea how to make my life meaningful, much less hers, I wanted to know what a meaningful life was, but I didn’t dare ask. For years I thought that my inability to make my mother’s life meaningful was why she treated me so badly. Once, when I told my father about my mother’s violence he said, “Talk to your mother,” which was impossible. I learned that whatever happened was always my problem, never my mother’s, no matter the damage. My father never stopped protecting her, even when he was critically ill, days away from dying. When the two of us were alone, I asked, “Dad, there are things about my early life I’d like to know.” His response: “I don’t want to talk about it, it would only hurt your mother.” Shocked, I asked again, reminding him that he was the only one who could tell me. Once again, he said, “I don’t want to talk about it, it would only hurt your mother.” At least he didn’t say, “Nothing happened.” In my world there was no refuge inside the house from my mother’s violence and abuse, or outside, where I was confronted by anti-Semitism and anti-communism. I retreated into myself, creating stories in my mind that comforted me, inventing a world in which I could not only live, but flourish. And yet, there is another side to this story, equally true, equally important. My parents loved music, dance, art, literature, and theatre, often taking me to various performances and art exhibits, much to my delight. I had dance, music, and piano lessons. My father loved Shakespeare and sometimes we would read parts of plays together. Between the late 1920’s and mid-1940’s my parents were communists, working to achieve social and civil rights—programs like social security, free milk for children, 8-hour working days . . . When my father was home, he and I listened to the nightly news on the radio and at the end of the program he would ask what I thought, what might be true, or not, and how I knew. If I didn’t have an answer he would prod me, saying silence was not acceptable. When the communist party stopped focusing on social issues in the US, my parents left the party. However, in this country, once a communist always a communist no matter what. They were unable to get passports until Paul Robeson sued the US government in a class action suit. When he won, and his passport was returned, my parents were able to get their first passports and travel outside of the US—something they weren’t able to do until the late 50’s. Days before my father died, I drove them to the bank, where much to my astonishment, I learned my mother’s name was not on any of their stocks and bonds, nor other assets. When I asked my father if he would put my mother’s name on them, he said, “No!” How could this be? They’d been married 47 years, in a supposedly loving marriage. The morning after my father died, my mother drove me to their bank with instructions as to how to take the money out of their safety deposit box. I felt like a thief, stuffing the two hundred dollars in my bra. When I got into the car she asked for the money and said it was all she had to live on until the will was settled. My mother was not submissive. I had heard her yelling at my father, especially when his stock market choices lost money. And yet, she allowed my father to put his name only on all their assets except for the house in the country and the condo in which they lived. It made me wonder what their marriage was really like.

Perhaps because of the abuse I suffered, as well as my parents’ political interests, I developed a strong social conscience very early—imagining a huge scale somewhere. If I did something wrong, evil would flourish, if I did something right, good would flourish. It was my job to make sure I kept the scale tilted toward good. No doubt my parents’ love of the arts fostered my interest in creating and making music, art, dance, literature, and theatre—passions that became the basis for my professional life as well as a lifelong source of joy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Monthly StoriesStories inspired by world tales to challenge and comfort. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Copyright © Nancy King 2020 | Site Design by Angulo Marketing & Design

|

|

Nancy King is a widely published author and a professor emerita at the University of Delaware, where she has taught theater, drama, playwriting, creative writing, and multidisciplinary studies with an emphasis on world literature. She has published seven previous works of nonfiction and five novels. Her new memoir, Breaking the Silence, explores the power of stories in healing from trauma and abuse. Her career has emphasized the use of her own experience in being silenced to encourage students to find their voices and to express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with authenticity, as a way to add meaning to their lives.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed